A bit earlier in the semester, I taught Sophie Treadwell’s 1928 play Machinal. It is the story of a woman who, in order to escape an oppressive life, finds a lover and eventually murders her abusive husband. The play was based on the life of Ruth Synder, who had been executed just a few months before the premiere. At the time, Ruth’s story saturated the headlines, but there is one person who is often overlooked in the story: Ruth’s daughter, Lorraine Synder.

The details of the case are well-known: Ruth Snyder, a working class daughter of immigrant parents, married a relatively affluent husband, Albert Snyder. He was emotionally and probably physically abusive. For example, when she gave birth to a daughter, he blamed her for not producing a son. He even hung a portrait of his ex-wife (who he named his boat after) in their bedroom. It is not surprising that she searched for love elsewhere and began an affair with a salesman named Henry Judd Gray. Shortly after secretly taking out an insurance policy on her husband, Ruth and Gray murdered Albert Snyder. If that sounds familiar, it is the plot of the film noir masterpiece Double Indemnity, in which an unscrupulous seductress manipulates an upstanding insurance salesman to murder her rich husband. James M. Cain was inspired by it to write his classic The Postman Always Rings Twice.

The night of the murder began like any quiet, normal evening. Ruth had dinner, put Ruth to bed, and then Gray entered the house. The pair tried to make the murder look like a botched robbery, but their plans went wrong from the start. They eventually drugged, garotted, and bludgeoned Albert Snyder to death. To make Ruth seem a victim, Gray tied her up and fled.

That night’s sleep was interrupted for Lorraine when she heard knocking from outside her room. When she emerged, she encountered a horrifying scene: her father was dead and mother tied up and gagged. Ruth told her daughter to go get the neighbor, who called the police.

Outside of the rather shocking manipulation of Lorraine, Ruth and Gray made significant mistakes from the start. Namely, they didn’t steal anything or disturb the house in any other way. In short, the police determined that the crime scene looked nothing like an attempted robbery and were immediately suspicious of Ruth.

In the play, the character of “Young Woman” is inherently sympathetic. Treadwell was pushing back against the pervasive misogyny that marked how the press and public saw Ruth Snyder. She was typically depicted with names like “The Marble Woman,” “the Bloody Blonde,” or “Ruthless Ruth, the Viking Ice Matron of Queens Village.”

One newspaper depicted Ruth as, “a poisonous snake, [who] drew Judd Gray into her glistening coils, and there was no escape.” The New York Mirror hired a phrenologist (that old pseudoscience) to diagnose her from photographs. He determined that she had:

The character of a shallow-brained pleasure-seeker, accustomed to unlimited self-indulgence, which at last ends in an orgy of murderous passion and lust, seemingly without a parallel in the criminal history of modern times.

By contrast, Henry Gray was treated with sympathy by the press as a victim of Ruth’s “hypnotic coercion.” Even the prosecutor called Gray a “decent, red-blooded, upstanding American citizen” who had the misfortune to have been manipulated by an overbearing woman.

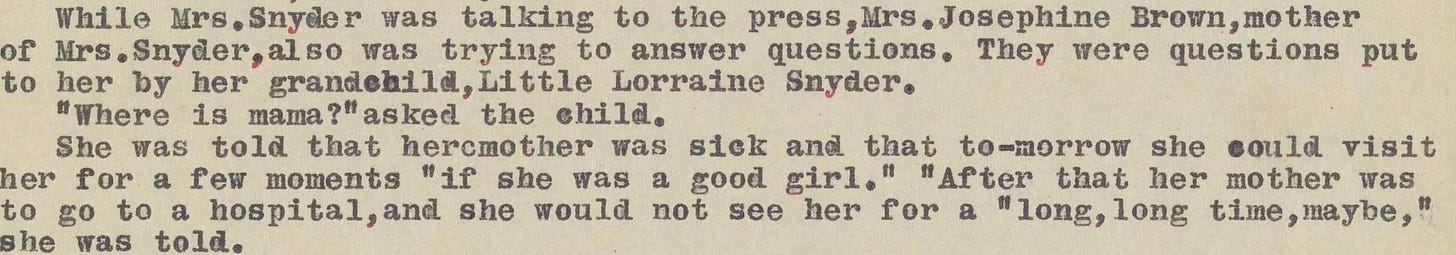

During the trial, Ruth’s daughter Lorraine, aged nine, was kept in the dark by her family about her mother’s role in the murder. If the newspapers were to be believed, Lorraine was never told that her mother was in jail or on trial. Here is the Woods Detective Agency’s observation of an incident during which Ruth’s mother, Josephine Brown, was talking to the press:

While the press followed the trial in minute detail, it paid some attention to Lorraine, largely fascinated by whether such an evil woman could raise a “normal” child.

At one point, there was speculation that Lorraine might testify. Ruth initially declined, as she did not want subject her daughter to the ordeal but changed her mind when it became clear she was losing the trial. Lorraine’s appearance was limited to a couple of questions only and it is not clear if she even understood why she was being called to the packed courtoom.

Eventually, Ruth and Gray were found guilty and sentenced to be executed in the electric chair. Still, no one told Lorraine what was happening. The night before Ruth was executed, she wrote a letter to her daughter explaining things from her point of view to be opened “when she was old enough to understand.” Gray, on the other hand, wrote 11 letters to his daughter, one to be opened on each of her birthdays until she was 21 (which I find fairly morbid and controlling).

Ruth was the first woman to be killed in the the electric chair in New York. The press was so fascinated by her death that one reporter rigged a camera on his shoe to photograph Snyder during the execution. It was illegal but it appeared on the front page of New York Daily News on January 13, 1928. The press hailed him as a hero.

A couple of days later, Lorraine’s family told her that her mother had died of an illness.

According to the news, “For hours, Lorraine wept bitterly, teachers and school mates being unable to console her.”

Next time, I will look at what happened to Lorraine in the years after the murder, as she was embroiled, at age 10 in a desperate legal battle for her survival.